At the Edge of Summer: Sailing South Through British Columbia

A late season coastal transit shaped by lighthouses, storms, and the first hints of a new chapter ahead

There is a particular tenderness to a southbound passage in late summer, when the first hints of autumn settle into the rainforests and the days begin to shorten around the edges. British Columbia became our threshold between worlds: the place where we left behind the familiar rhythm of Alaska and slipped into the unfolding unknown of our long sailing journey ahead. We were between seasons, between Alaska and the rest of the United States, and between chapters in our own lives, carried forward by tides that felt as much internal as they were geographic.Going to Canada was something I was especially excited about because, for all the traveling I’ve done across North America, I had somehow never actually been to Canada. I’d flown over the British Columbian Rockies countless times on my way to Alaska, been five miles from the border crossing in Haines, and even took the ferry through its waters aboard the Alaska Marine Highway when I first moved north. But despite all that proximity, I had never set foot on Canadian soil.It struck me how similar coastal BC felt to Southeast Alaska, with its misted fjords, verdant forests, and quiet anchorages tucked into cliff-lined inlets. The mountains softened as we headed south, their slopes more rounded, their presence less abrupt. Even with the rain, I felt a constant hum of excitement about the adventure ahead: inching closer to the Pacific Northwest and on toward Mexico’s Sea of Cortez. For me, it was my first time sailing internationally; For Louie, who had sailed from Alaska to Panama years before, these were familiar waters. I wondered what this next chapter of our lives would bring and where we would be a year from then. (Spoiler: I’m writing this now on night watch as we sail to New Zealand.)PRINCE RUPERT

As we neared the port town of Prince Rupert, we passed by Green Island, a rocky outcrop crowned by a lighthouse complex, its red-and-white Canadian flag rippling in the wind. Its white walls and red roofs gleamed against the dark stone, and from certain angles it looked like a castle perched above the sea. It was the first unmistakable sign that we were, at last, in Canada.We arrived at the customs dock at Cow Bay Marina in full parade dress, Arcturus flying flags for Canada, British Columbia, Alaska, our cheeky “Just Married” flag, and the Juneau Yacht Club burgee. It made us laugh to think we were still, technically, on our honeymoon. After a very relaxed phone call with Canadian Customs, we were instructed to simply write our clearance number on a slip of paper and tape it to the window. No in-person inspection, no fuss.We checked the sailing app NoForeignLand and noticed a catamaran listed in the harbor. A quick glance up and there it was: S/V Amaryllis, moored right in front of us. I messaged the couple aboard, who warned us not to fill water at the dock due to a recent pipe burst. They even offered us water from their rain catchment if we needed it – Sailors never cease to surprise me with their generosity.Prince Rupert greeted us with familiar coastal rain. Louie’s friend toured us around town, pointing out vibrant murals, introducing us to the pilot boats he worked on, and finally driving us to the North Pacific Cannery National Historic Site of Canada. Perched on stilts over the Skeena River, the cannery preserves the ghost-hollow hum of a once-bustling salmon empire. Its weathered wharves, bunkhouses, net lofts, and mess hall still carry the rhythms of fishermen arriving at dawn and nets hauled from the water heavy with salmon. Founded in 1889 and now Canada’s oldest surviving west-coast cannery, it stands as a wooden testament to nearly a century of industry, built by the labor of European, First Nations, Asian, and immigrant workers until operations ceased in 1981.Much of our short stint in Canada was marked by steady rain as the season shifted, turning small streams into rushing rivers. We found ourselves trying to savor the last of the Alaskan summer while also needing to get south to Bellingham, where I had to fly from to shoot weddings in California in October. With work on either end of the voyage, our not-quite-two-week passage through British Columbia became a steady, purposeful push.BISHOP BAY HOT SPRINGS

Making our way south in search of hot springs to offset the rainy chill, we traveled down Grenville Channel toward Bishop Bay, stopping for the night in Lowe Inlet’s Nettle Basin. Hot springs are one of the luxuries we missed earlier in the summer while exploring Prince William Sound, the Kenai Peninsula, and Kodiak. They’re plentiful in Southeast Alaska, and that abundance continues along the BC coast. Pressed for time, we managed to visit only one: Bishop Bay.On a day that alternated between rain and sudden bursts of light, we wound through a labyrinth of fjords surrounding Gribbell Island. Each turn revealed either a passing rain shower or yet another rainbow. I thought of that as the day of rainbows, as light and water braided themselves through the pines of the Great Bear Rainforest, which stretches the whole length of the coast. The world seemed to shimmer between storm and calm.Tucked deep into the bay, the The Bishop Bay Hot Springs bathhouse offered shelter from the elements while still welcoming the wildness around it. Flags and keepsakes from sailors of years past lined the walls and rafters, forming a mosaic of stories left behind. Each item carried a vessel’s name, a date, and a memory. Looking around at the collection of weathered trinkets and flags, I started to feel part of a larger seafaring community. Bathed in a rare patch of afternoon sun, we soaked in the warm water and felt the weight of the previous days melt away. Having the springs entirely to ourselves felt like a small blessing after peak season.And of course, no account of sailing BC would be complete without acknowledging the floating logs—so many logs. They are the legacy of a century of coastal logging, where timber was historically transported, stored, and sorted directly in the water. Log booms routinely broke apart in storms or strong tides, and natural forces added even more debris: heavy rains, landslides, and erosion sweeping fallen trees into rivers that carried them to the sea. Mariners here must always keep watch, dodging stray logs and entire rafts that wander freely with the currents.STORM AT SEA

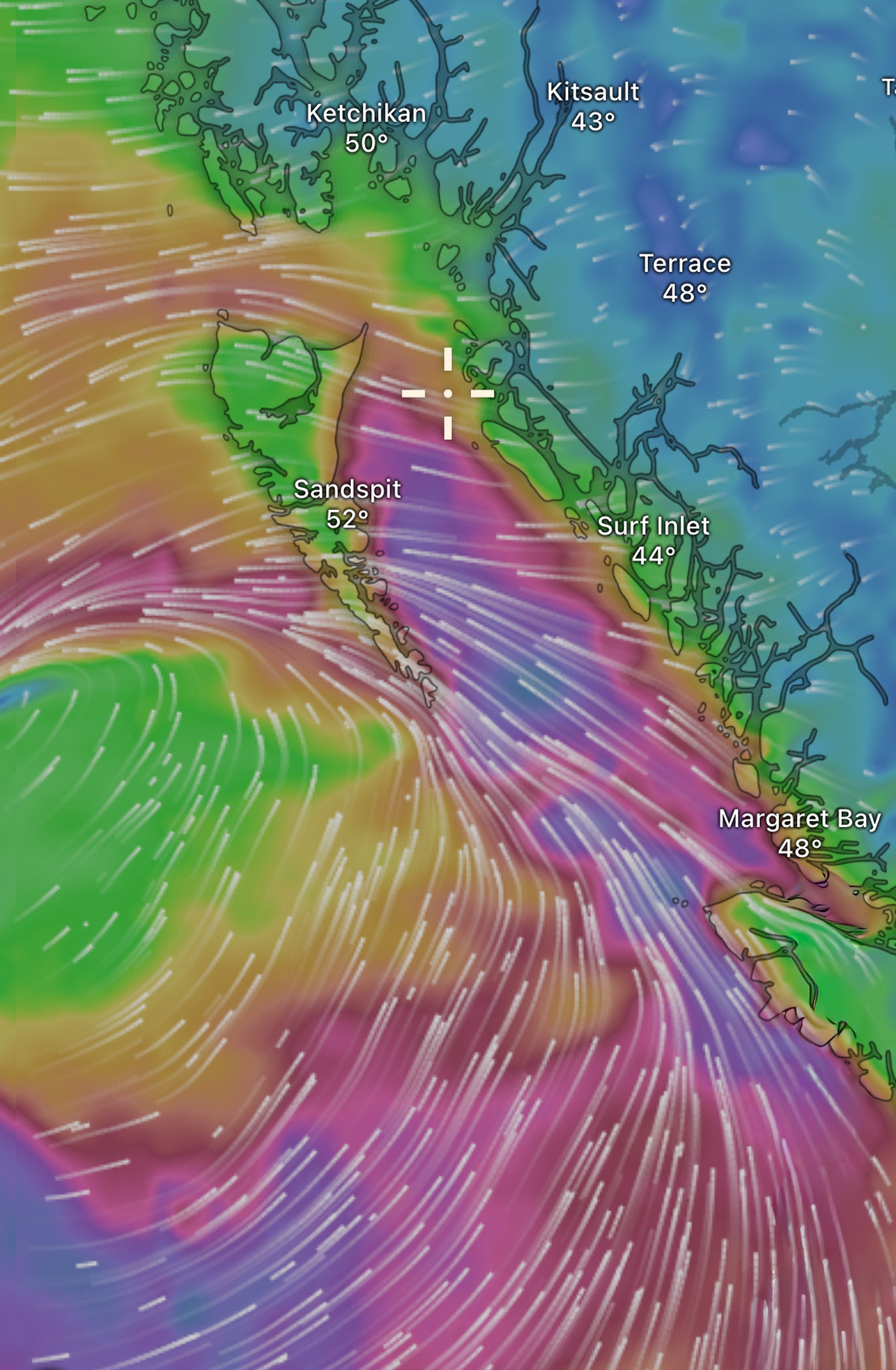

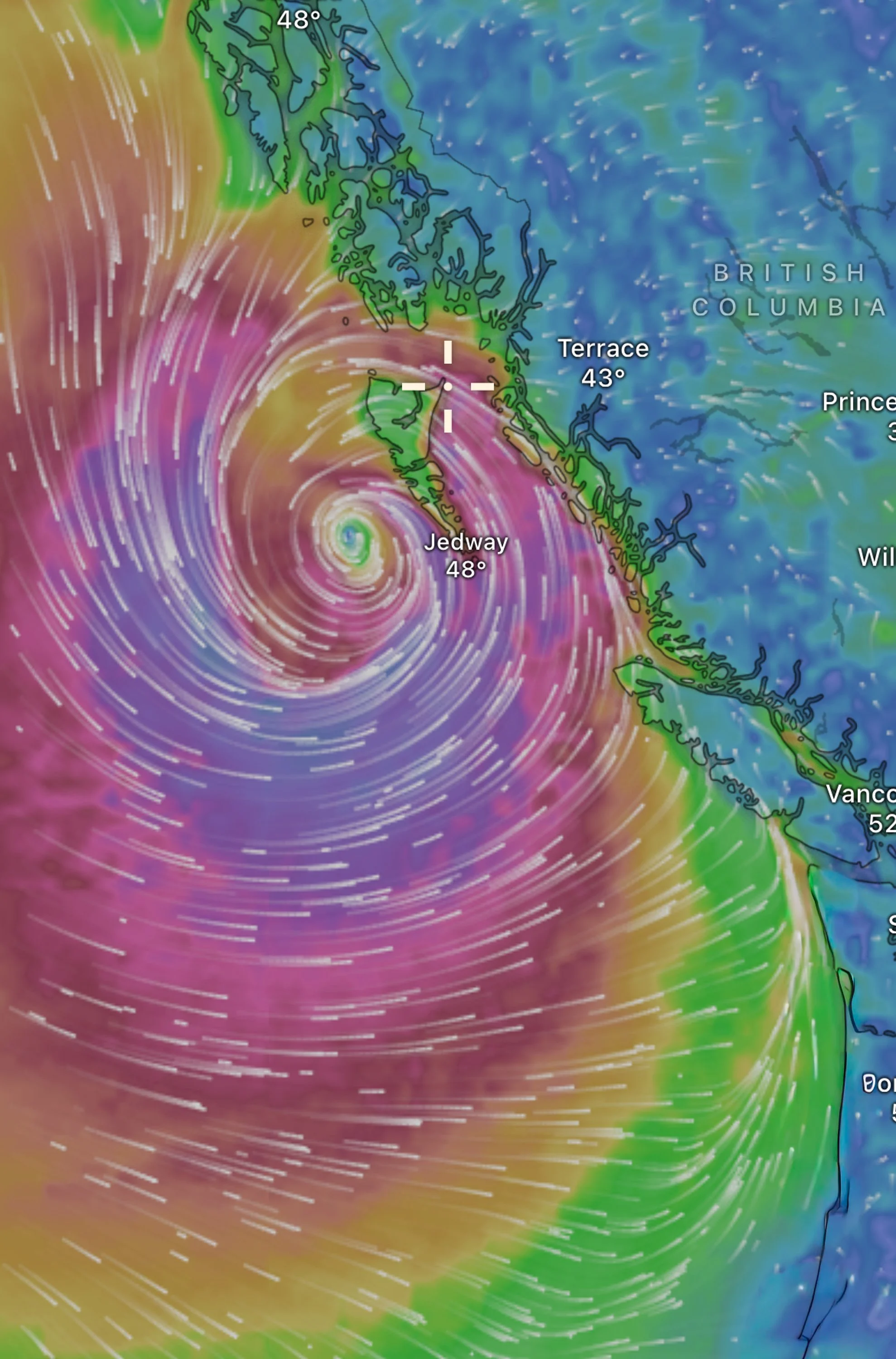

By the halfway mark of our journey, we faced a new challenge: an approaching storm. We monitored the forecast closely, waiting for the first gusts. When none arrived by late afternoon, we made a firm decision to push onward just a little longer, leaving the Seaforth Channel and crossing the exposed stretch toward Milbanke Sound before conditions became unpleasant that night and kicked up waves the next day. As the sun dipped below the horizon, we passed Ivory Island Lightstation in the last warm glow of daylight.We pulled into a small, sheltered cove, believing we’d outrun the storm, but the night was just beginning. Darkness fell as we prepared to drop anchor, and the wind began to build. By the time the anchor touched bottom, we had already drifted uncomfortably close to shore.We tried again in pouring rain and rising gusts. The wind made it difficult to find a safe position between the neighboring island outcrops to drop. I was stationed at the bow, shining my flashlight at the surrounding islands to give Louie bearings in the blackness, as our GPS couldn’t tell which direction we were facing at such slow speed. In the chaos, the anchor never fully deployed; we hadn’t pushed it over the bow before letting the chain run. It wasn’t until Louie reached the bow that we realized the chain had piled in a tangled heap around my feet. We tossed the anchor manually, hoping it would catch. It didn’t, and the strain sheared the bolts on our windlass.With the winds howling and the rocky shore far too close for comfort, Louie took the helm and walked me through our only option: retrieve the anchor manually, foot by foot, using the mast winch and a hook to the chain. Rain stung my face as I cranked with all my strength. Louie dashed between the helm and the mast winch to help, then back again to steer us off the rocks. After what felt like an eternity but was likely under ten minutes, the anchor was finally back aboard. We motored out into the Inside Passage, back out to the storm, soaked and exhausted and happy to have not ended up on the beach that evening.The nearest refuge was Shearwater, three hours away. Louie encouraged me to take a hot shower and get dry, as there was still a long few hours ahead. Waves crashed over the doghouse windows as we pushed through the storm. I was grateful we weren’t out at sea, but I couldn’t stop thinking about the floating logs lurking unseen in the dark. Near midnight, the winds began to ease as we approached Shearwater. The harbor office was closed and the harbor master was away on holiday, but we managed to reach the local pub by phone, and the bartender told us the harbor was likely full but that we might tie up to the breakwall if needed. We spotted an empty finger, but a man in rain gear waved us off, shouting, “Not safe! Not attached!” The storm had broken it loose hours earlier.We turned toward the breakwall, visible only on radar and satellite imagery. Louie sent me forward with my headlamp to spot it.

“See anything?” he called.

“Not yet!” I yelled. Seconds later I shouted “Full stop!”Looming ahead was a massive raft of – get this – about two hundred logs, chained together… Shearwater’s very Canadian interpretation of a breakwall. Arcturus gently bumped over a few logs before drifting back. We determined there was certainly no tying up there for the night. Near 1 a.m., we finally found refuge beside the fuel dock and adjacent floatplane dock, which was also loosely attached at best. But it was enough to sneak in a few precious hours of sleep before continuing.CALVERT ISLAND & THE HAKAI INSTITUTE

We departed early the next morning, weary but grateful, bound for Calvert Island and the Hakai Institute. Tucked into the wild edge of the island, Hakai is a modern observatory where science meets salt and spruce. What was once a remote fishing lodge now pulses with marine-ecology research, forest monitoring, and deep-time environmental awareness. Even the lingering swell from the storm felt softer under the bright morning sun.Once anchored in Pruth Bay, we hauled our anchor locker contents onto the deck to replace our chain with rope until we could install a new windlass. A man on the Hakai dock waved us down, urging us to call on channel 16. The dock manager invited us to tie up where float planes normally stayed, as no traffic was expected that day. As we docked, we noticed one of our solar panels dangling by a single screw – we must have looked to be quite a sight.The dock manager greeted us warmly, telling us to take all the time we needed to sort things out. A fisherman at the dock was dealing with his own engine issues. Another charter boat nearby had also lost their windlass. “Quite a wild early-season storm,” their captain said. We felt in good company with the other wayward boats after weathering the storm.After putting things back together and deciding to get off the boat to head out for a sunset walk, we walked up the dock to be greeted by a man with a friendly smile and offered us a tour with the other charter boat who usually rain tours there but was crew only as they had just finished their season. The man turned out to be the founder of the Tula Foundation, which created and funded the institute. His enthusiasm was contagious as he showed us the sustainable gardens, living systems, and research facilities woven seamlessly into the wilderness.The Hakai Institute is the flagship vision of the Tula Foundation, founded in 2001 by Eric Peterson and Christina Munck. Their belief that wild places deserve both guardianship and curiosity grew into something far more ambitious when they acquired the old fishing lodge in 2009 and transformed it into a world-class ecological observatory. Tula’s work now spans marine ecology, watershed and cryosphere research, environmental genomics, and a network of long-term monitoring programs connecting scientists, First Nations partners, and coastal communities.After seeing the institute’s trail system, we walked the trail system under soft, misty light. The air was misty, still tasting faintly of salt, glowing with the post-storm clarity of sunlight after rain. The Hakai trails were beautifully maintained, winding through cypress and muskeg to the rugged shore where sandstone met granite, and the still churned up ocean waves crashed rhythmically against the cliffs. It was a place that felt both wild and quietly sacred.THE PASSAGE SOUTH, Lighthouses, & DRIFTWOOD CABIN

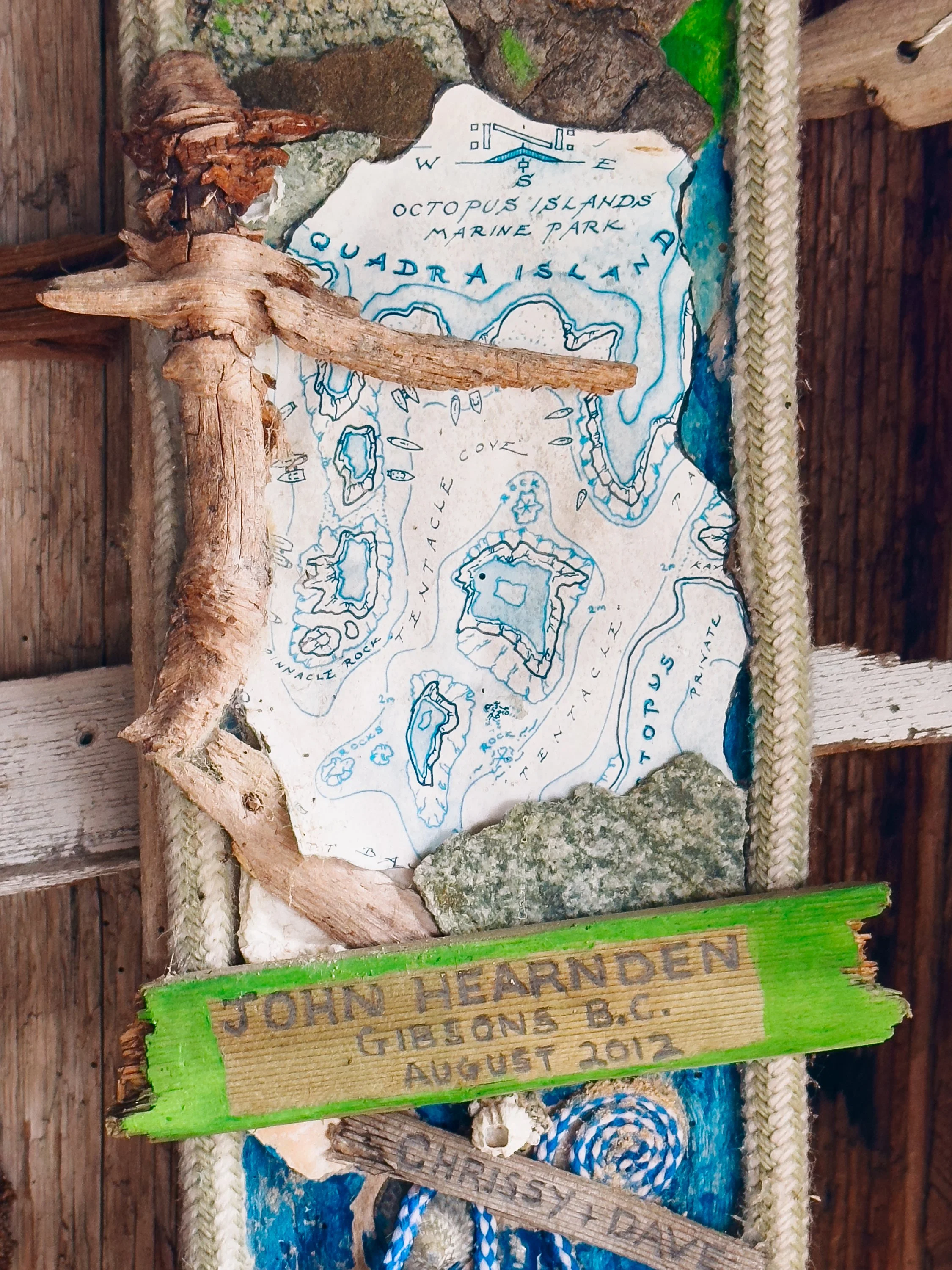

From there, our southbound journey blurred into long days through narrow channels and lighthouse-dotted headlands. We passed Pine Island Lighthouse, then Pulteney Point Lighthouse, their red roofs and white towers appearing like small, steadfast companions guiding us onward.Johnstone Strait led us east beneath blue-shadowed cliffs, the water reflecting their color like a mirrored fjord. We spent a quiet night at the Shoal Bay government dock on East Thurlow Island, encircled by granite peaks that glowed pink and lavender in the alpenglow. The air was still, the water glassy, and for the first time in several days it felt like the coast was giving us room to breathe again.The next morning, we continued through Devil’s Hole to Dent Rapids, Gillard Passage., and Yucca Rapids The currents roared beneath us, swirling and twisting like something alive. It felt, truly, like sailing through a real-life Pirates of the Caribbean ride: rapids, whirlpools, towering cliff walls, and the exhilaration of navigating narrow waterways that demanded respect and attention. Arcturus handled it with grace.Before leaving British Columbia, we visited the Driftwood Cabin in the Octopus Islands. Hidden among mossy firs and tide-carved rock, the cabin is a humble sailor’s refuge filled with driftwood plaques, carved initials, flags, and trinkets left by wanderers over decades. Its walls feel alive with quiet stories. It reminded me of Bishop Bay’s bathhouse, another communal hearth for mariners carried by wind and tide… A pirate’s hideaway in the wilderness.NEARING THE CITY

With time closing in before we had to reach Bellingham, we made our final push toward the city. In Comox, we met mutual friends from New Mexico and wandered the charming waterfront streets. The marina and the town Comox felt warm and inviting, with small bakeries and cafés tucked between art shops and marina walkways. Our final Canadian stop was Nanaimo, where we moored at the yacht club. The harbormaster was, fittingly, out of town, and we hadn’t been given an access code to exit the gate, so we took the dinghy to the public dock and found a cozy brewery-pizzeria just outside the downtown area. The staff delivered our pizza shaped as a heart, another unexpected honeymoon moment.We crossed the border via a simple video call with US Customs, no in-person check-in needed. The coastline ahead opened into the long stretch of the Pacific Northwest and our southbound journey toward the West Coast of the United States. British Columbia had been our threshold, and now we were stepping into the next new chapter of the journey.Adventures, Words & Photos by Lerina Winter & Captain Louis Hoock

Originally Published: DECEMBER 6th, 2025

Search for Treasure and Explore BRITISH COLUMBIA

Treasure of British Columbia

Sale Price:

$149.00

Original Price:

$199.00

See Where S/V Arcturus is now on No Foreign Land: